In Her Hands: The Birthright of Being a Female Business Owner

By four years old, I’d memorized the silhouette of my Nana, bathed in flickering blue light, spilling over the sides of her bucket chair, positioned in front of her sewing machine in the garage. She’d sweat through personal projects: serging patterned dresses that I usually refused to wear; “letting out” my grandfather’s slacks as his portly stomach continued to pour over the waistband of his khaki pants; and stitching projects she’d been petitioned for by the women’s auxiliary group—always with a needle tightly pressed between her lips.

No matter how relentless the Texas heat, I’d camp out inside that garage with her to watch her work—my chubby thighs sticking to the sides of a little blue plastic chair, leaning into the stream of air from her rickety, sputtering fan.

“You want to sort buttons for me?” She’d ask. No matter how many times I’d sifted through her large, clear jar of mixed buttons, I always agreed. I would spend hours lumping them into categories: size, style, color, or shape. There were hundreds. I would organize them until night fell and my back ached from being slumped over in concentration.

Once our hard work was done, we’d reach a “stopping point,” go wash up, then stand practically naked in front of her window unit to “cool ourselves” until it was time for bed. Then, we’d read a few pages of A Cricket in Times Square until we drifted off to sleep. I’d always wake up to find her pouring my grandfather’s coffee and asking him what he wanted for lunch between big, savory bites of breakfast casserole.

At a young age, I gathered caretaking was not only my Nana’s role—it was her whole identity as a pastor’s wife: cooking, cleaning, sewing, catering to my Poppy as he sat in his lumpy brown chair, and loving me. What else could she have wanted? It would be more than one decade before I’d come to wonder who my Nana would have been if she hadn’t gotten pregnant at sixteen. It would not be until I became an adult and a business owner that I would recognize the intergenerational trauma of the women in my family, the brilliance of their creativity, and the pain of their extinguished dreams.

The first time I deeply hurt my Nana, we were standing in the Cedar Park tag agency. Small and restless, I was obnoxiously wiggling, trying to occupy myself as we waited in line. Once it was our turn, the woman on the other side of the desk offered me candy; I took a piece of taffy as she began speaking with my grandmother.

“Okay, I’m going to need to see your identification. And what is the name of the business you are here to register?” The woman asked.

“Yes, my name is Neva Woody,” my grandmother responded, “and my business is called Neva’s Needle!” Despite being very little, I could sense the elation and pride in my Nana’s voice. I’d never seen her smile like that about anything, and it made me uncomfortable. It didn’t feel “allowed.” Feeling confused and betrayed by this, as though my own grandmother was a stranger, my little mouth snapped,

“Your name isn’t Neva! It’s Nana! And you don’t have a business! You just sew my dresses!”

Her dejection at my words stays with me two decades later. I’ll never forget how she winced in anguish as though I’d pressed my finger into a tender bruise.

“Jade, I am a business owner,” she said with all the strength in her body, “My name is Neva. Not Nana. I am a seamstress for a living. I sew clothes. Not just your clothes. People pay me money for the clothes I make. That’s what makes it a business,” she concluded.

Intuiting that I had crossed an invisible line, I was covered in shame. I nodded to indicate that I understood but kept my eyes on the speckled floor as my cheeks burned with embarrassment. We sat in silence the whole way home.

Throughout the following decades, I’d wear everything my Nana made me: elephant bellbottoms, poodle skirts, coveralls, and even my prom dresses. “Promise me you’ll make my wedding gown—” I’d beg, with a specific Butterick pattern in mind. “I promise,” she’d say, even as her health began to decline.

Nana died when I was twenty-four due to infected bed sores after having triple bypass surgery. When I touched her hands on the day of her funeral—I knew she’d died of a broken heart. She’d been demonstrating signs of depression for years after developing carpal tunnel in her hands. To save Neva’s Needle, she put her faith in the hands of a surgeon who botched the procedure. Despite her best efforts, she couldn’t will the effort to sew again; at best, she stitched quilts in her rocking chair until her death. I estimate the loss of my grandmother was psychosomatic. Once disconnected from her creativity, her soul withered until she disappeared entirely.

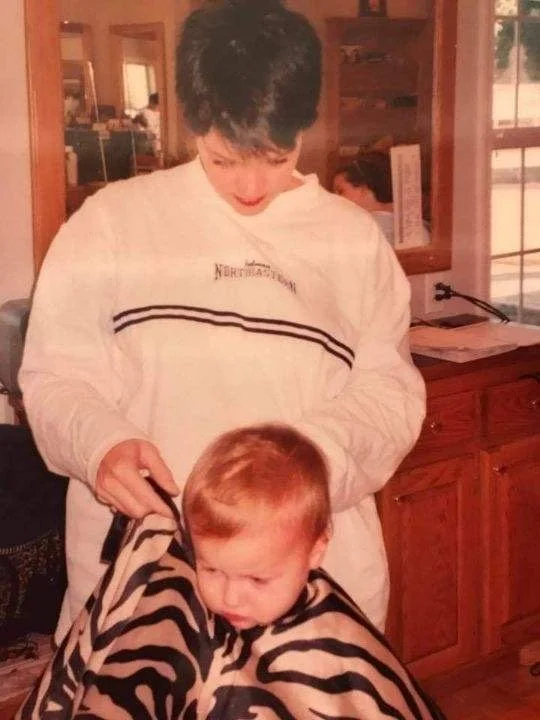

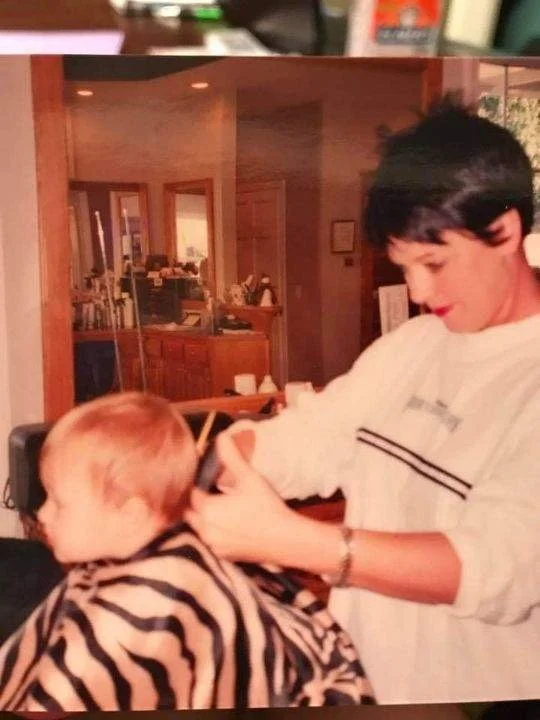

I saw the same thing with my mother, who owned her own business as a cosmetologist. Some of the earliest memories I have of my mom are of her hovering over her clients in the dingiest barber shop in all of Norman, Oklahoma: The Mane Man. The place reeked of cigarettes, acetone, and men’s aftershave. I’d watch her from the busted-up leather sofas covered in decades’ worth of hair and dust while she stood on her feet for hours—counseling clients, absorbing their stories, taking phone calls, managing her books, radiating energy, light, and laughter the entire time—making an exhausting job look easy.

By the end of every haircut or color, she’d swivel her client’s chair around for the “big reveal.” More often than not, her clients would beam with newfound confidence or burst into grateful tears. Because my mother wasn’t just a hairstylist. She was an artist. Beyond mastering her craft, she possessed the innate and whimsical gift of drawing out the intrinsic beauty of others. This gift would preserve her clientele throughout countless, inevitable moves that eventually ended my parents’ marriage.

The running joke about being a football coach’s family is that it’s really no different than being a military family. If the team wins, you move. If the team loses, you move. We moved across Oklahoma nine times before I was in middle school—leaving my mother’s business devastated every time. Attached to her clientele, she’d lug her supplies across the state on weekends to maintain her business relationships. She made a name for herself in countless cities: cutting hair in multiple shops and in our own home until, eventually, my parents divorced, and we settled in Norman, Oklahoma, where we stayed throughout my high school years.

Our home was more modest during that time than any we’d lived in. We didn’t have internet or cable. We learned what we could live without. Instead of watching tv, we’d listen to music and paint in the backyard. We downgraded from being a double-income, upper-middle class family with a swimming pool to a family living just above the poverty line.

And we were happy.

If there’s one thing I can say about my mother, it’s that she made sure I never had to want for anything. I can’t count how many times I’ve said, “I think we were poor, but I didn’t know it. If we were, I never felt that way. We were rich in love.”

Once I went to college, my mother went on to pursue her dream of becoming a cosmetology instructor. I got to watch her change lives and finally make the salary she deserved as an educator at South Plains College—the most prestigious cosmetology school in the South Central United States. I love telling her story because, just as it was my grandmother’s birthright to establish her business, it was my mother’s birthright to creatively, emotionally, and financially thrive—even amid difficult circumstances.

“. . . But your mother was no real contribution to society,” Jake said. We were sitting on my couch as he said this, and my blood went cold. I have to have misheard him, I thought. We’d been seeing each other for a turbulent three months, in which we’d broken up and gotten back together five times. By that point, I was used to his denigrative commentary. He generously elaborated that he was evaluating her work from an economic standpoint alone, that it wasn’t a value judgment, “She just didn’t make a lot of money, so . . . she wasn’t a contribution to society,” he concluded.

“Well, you work in tech, so I make less money than you. Does that mean my job is not as important as yours?” I asked. Jake evaded the question but went on to state, “I think you glorify writing . . . the way you’d put your dream over your family is selfish. I can’t see that being with a self-employed freelancer would be good for the long term.”

As the words slipped out of his mouth, a familiar anguish enveloped me—a sadness so thick, I could hardly breathe. My mind flashed to Nana’s face in the tag agency—registering her business, then to my mother’s, who rebuilt her clientele after every move, devastation, and loss. I reasoned that if I had to spell out to Jake what my dream meant to me, he wasn’t a love worth keeping. If he deemed my aspirations “small” or “selfish,” he would be lethal to my purpose. So, I chose to live out my legacy instead, understanding it might be lonely.

There are countless reasons never to become a freelancer, and there is always someone there to remind you of the ways you might fail. It’s scariest when those are the people closest to you—no matter how well-intentioned.

Over time, you learn that metabolizing others’ opinions and concerns is just another challenging part of the job. I can’t tell you how many sleepless nights I’ve spent worrying about the future. What if I lose all my clients? What if I am never approved to buy a home? What if I have a dry spell? What if I never retire? What if this is just a fluke? What if I’m deluding myself?

Indeed, as a single female in my thirties, the stakes feel higher. But the beauty of the ghostwriting industry is that it’s female-dominated. I have four strong, dynamic mentors from unique walks of life who have given me endless counsel and gorgeous examples of the life I want to lead. They have shown me how to actualize my dreams, even on bad days. And if I ever need encouragement, I reflect upon my grandmother and mother: who they were, what they sacrificed, and the careers they built. Because of them, I know I’m not alone.

A few months ago, I was sitting in bed, trying not to call Jake. Needing a hug, I wrapped up in the last quilt my grandmother stitched before she died. Suddenly, I felt something sharp poking my arm. I looked down to discover a hidden treasure sticking out of the threadwork: the last needle my Nana had ever used. She was there, not only holding me but (very sharply) prodding me toward my birthright—pointing me to become the woman I was made to be.